Cohesion, Crisis, Revitalisation, and More Crisis - The Eighties

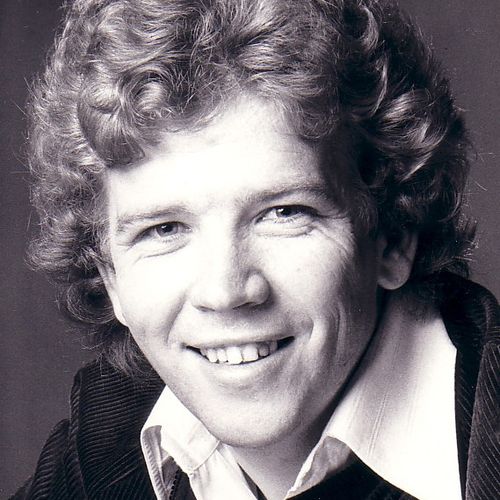

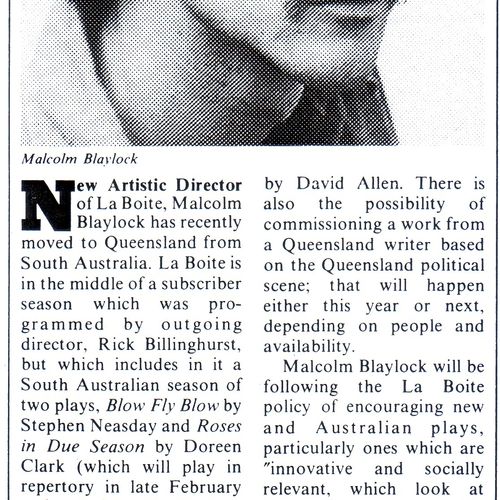

Initially, the early 1980s was a buoyant time for La Boite and for the pro-am theatre community in Brisbane. The new artistic director, Malcolm Blaylock, had reason for optimism.

In 1980 the Theatre Board of the Australia Council transferred La Boite from a project grant company to a general grant company, a coup (albeit short-lived) for La Boite making it the only pro-am Theatre on the general grants list, which included professional companies throughout Australia. Blaylock interpreted this success as “an unqualified endorsement” of La Boite’s “unique role amongst Queensland companies; firstly as a community theatre and, secondly as a company with a policy of supporting new and innovative works”[i].

Such optimism was short-lived however, as the following year its Australia Council funding was cut. The official reason given was that the Australia Council had had its own funding cut by the Federal Government, and could no longer afford to fund amateur companies like La Boite. Blaylock rejected this label of ‘amateur’ claiming “We are a Professional Community Theatre. Last year we employed nine people full-time and fourteen people part-time. Our professional salary bill for the year was second only to the Queensland Theatre Company” [ii]. He believed the sub-text to the cuts was that “innovative and developmental companies are not considered to be an important part of the theatrical life of this country” and “unfortunately the concept of a Community Theatre in which a large number of professionals work with and for the benefit of the community is not acceptable to the Federal funding bodies”[iii].

Faced with a potential catastrophe, La Boite’s constituency[iv] rallied in the first major test of its support and loyalty. Under Blaylock’s leadership, a tremendously powerful public campaign was mounted, resulting not only in funding restored for La Boite but increased Federal Government funding for the Australia Council. As Blaylock commented[v]:

The campaign to have La Boite’s funding re-instated was the most successful political exercise that I have ever seen in the theatre. The Chairman of the Australia Council, Timothy Pascoe in a meeting on Friday, 29th January 1982 with Jennifer Blocksidge and myself, stated that the government’s allocation of extra money to the Australia Council was due very largely to the effective campaign run by La Boite Theatre.

The writing was on the wall however - La Boite had to decide to return to a completely amateur theatre or become a fully professional theatre company.

Throughout these dramas, Blaylock pursued his largely successful artistic vision for La Boite by programming innovative, risky Australian and non-Australian plays, many with a clear political and socially critical agenda. Following the trend begun by Billinghurst, his 1980 season was all-Australian, a first for La Boite, and one that doubled subscribers. In this period dominated politically by Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen’s conservative government, productions with strong political messages such as Trevor Griffith’s Occupations and Stephen Sewell’s Traitors attracted the attention of the Queensland Police Force Special Branch. Happily for La Boite, Special Branch surveillance never translated into punitive State Government funding cuts.

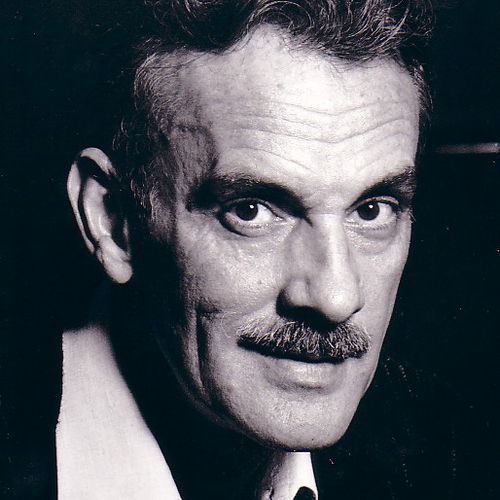

When Andrew Ross was appointed Artistic Director in mid-1982, his brief from La Boite’s Council, as he understood it, was to forge La Boite into a professional company. The exciting artistic work that he developed during his short time as AD gave promise to the view that La Boite could become the Nimrod of the North. Ross is credited with its first real foray into professional mainhouse productions, its first production of a commissioned work by a Queensland playwright, and its first season of three professional theatre for young people productions. But strong membership resistance to this push towards a professional company from an entrenched amateur culture, made for a volatile situation. Several troubled years for La Boite culminated in the devastating loss in 1983 of both the State Government and Australia Council Theatre Board grants.

Amazingly, the doors stayed open with a skeleton staff. A massive effort in 1984 and 1985 by the Council, particularly President Helen Routh, and newly appointed ‘resident directors’ (as they wished to be called) Mike Bridges and Mary Hickson, administrator Ron Layne, and executive secretary Rosemary Walker saw the restoration of Theatre Board funding and, incredibly, an ongoing artistic program. How La Boite managed its survival through the worst financial and policy crisis in its history was another classic example of La Boite’s power to rally support from its constituency. However, the enormous benefit of theatre ownership and a property portfolio cannot be underestimated in understanding how this crisis was surmounted; without the asset of the theatre building in particular, where amateur productions and other activities could proceed even without funding, it is doubtful that La Boite would have survived.

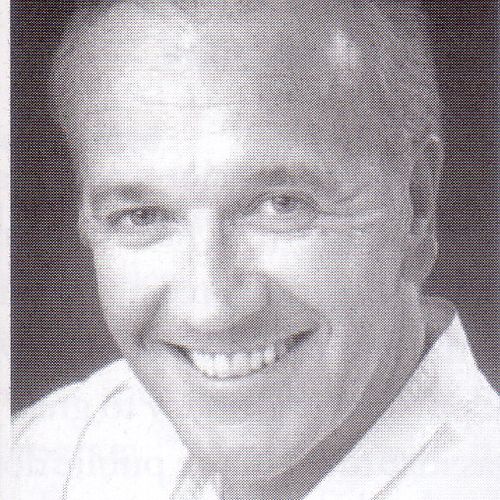

On Bridges’ and Hickson’s departure, the Council created a new position of Managing Artistic Director (M.A.D) appointing Jim Vilé in 1986 to this combined role of artistic director and CEO. Whilst funding imperatives kept theatre by and for young people as the Theatre’s major objective during Vilé’s artistic directorship, he understood and respected the ‘pro-am’ nature of La Boite and during his time main-house pro-am theatre flourished. In no small measure this flourishing was due to the active participation of professional artists attracted by the exciting programming and challenging performance space. To boost theatrical activity Vilé adopted a successful ‘Open Door’ policy at La Boite where “everything and everybody was encouraged to take part”[vi]. Theatresports was introduced; La Bamba, begun in 1982 as a late night cabaret-style event, was re-vitalized; tutors conducted workshops for every age group; and the space was hired out to appropriate companies. The level of activity that Vilé, staff and volunteers managed to sustain was extraordinary – every day and evening of every month of the Theatre’s year was accounted for with a production of some kind. No professional theatre company could have afforded to keep up this level of creative output; this was the great strength of Australian pro-am theatre at its best. No better demonstration of this was La Boite’s performance during World Expo ’88.

Adopting the slogan La Boite – The Biggest Little Theatre in Australia, Artistic Director Jim Vilé decided not to cut back his 1988 season in the year Brisbane hosted World Expo’88 and programmed seven big mainhouse productions. These, he said “provided up to 300 opportunities for theatre workers to be involved in really top plays, making serious and stretching demands on one and all”. La Boite finished up with the biggest program by far in Brisbane in the year of Expo, “pumping out more product than any similar sized organisation in Australia”.[vii] The reason La Boite could afford to take this gamble was its pro-am status. With no actors to pay, with the majority of directors giving their services for free or a small fee and front of house and backstage run by volunteers, it could afford to take risks not available to the two professional companies, RQTC and TN! His gamble paid off with an average 51 % occupancy, the best in his three years at La Boite, and a surplus of $25,000.[viii] His rationale was that La Boite was “constitutionally committed to service to the community” and, despite Expo ’88, “there were still people out there who wanted to act, to direct, to be directly involved and committed to theatre work”.[ix]

The biggest success of Vilé’s Expo season was Hamlet, directed by Robert Arthur with musical direction by Donald Hall. After the success of of his 1987 production of As You Like It, Vilé had no hesitation in programming another Shakespeare. In fact, its financial success meant Vilé could afford to pay a director’s fee to Robert Arthur, a highly regarded professional Brisbane director and actor, who attracted to his production of Hamlet “some of the most exciting established and potential talents in Brisbane”[x] including Eugene Gilfedder, Dianne Eden, Peter Lavery, Peter Knapman, Darryl Hukins, Charles Barry, Vassy Cotsiopoulos, Anna Pike and Julian St John, most of whom had worked professionally with TN! or RQTC. Both a critical and box office success, it rated 87% attendance. It would have rated at 100% if some nights had not been preserved for adults only. A big hit with schools, at least twenty school parties were turned away. The two other very popular productions with both general public and school audiences were Ray Lawler’s Summer of the Seventeenth Doll directed by Don Batchelor and Sue Townsend’s The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole directed by Sue Rider, featuring professional actors all working at La Boite for free.

By the end of the 1980s La Boite had reached a reasonably secure financial position once again, achieved through pragmatic programming, an increase in the quality of artistic work and conservative financial management.

However, the happy arrangement whereby professional actors practiced their craft for no pay at La Boite in between paid work, turned sour by 1989. At the time, this situation was unique to Queensland, the only state in Australia where Actors Equity of Australia (later Media Entertainment & Arts Alliance) permitted professional actors to perform in unpaid, amateur productions[xi]. The year before, Aubrey Mellor had succeeded Alan Edwards as Artistic Director of the Royal Queensland Theatre Company and was moving swiftly to revitalize the company and embrace actors who had previously found professional work mainly with TN! and non-paid work with La Boite. His attention focussed sharply on La Boite when he witnessed three of the five prestigious Queensland Matilda Awards going to professional artists for work undertaken in amateur productions. As Vilé recalled, Mellor soon “started to stir the pot and there were lots of people willing to listen to that and quite rightly”[xii]. Vilé felt uncomfortable with his role in perpetuating this situation although pleased that he was able to mount two professional productions (Crystal Clear and The Matilda Women) which he saw as a bridge towards a much needed decision by La Boite to become a fully professional company.

One of a number of issues that contributed to difficult time for Patrick Mitchell, who in 1990 succeeded Vilé as Artistic Director, was the same one that had dogged Vilé: industry pressure for La Boite to pay its actors and production staff. Only several days into the job this simmering issue erupted when three of the five Matilda Awards once again went to professional artists for their unpaid work in La Boite productions. He recalled that “the profession was outraged” and he was in the firing line[xiii]. Coming from a professional theatre in education background, Mitchell found himself trying to manage a very active pro-am theatre company, trying to deliver everything Jim Vilé had delivered with less staff, less support and, most significantly, no General Manager. Mitchell dramatically announced his resignation at the gala launch of his 1991 season. It seemed that a move towards La Boite becoming a fully professional operation was now inevitable.

Writer: Christine Comans

[i] Artistic Director’s AGM Report 1981.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Managing Artistic Director’s AGM Report 1987.

[vii] AGM, March 5, 1989.

[viii] AGM Minutes, March 5, 1989.

[ix] AGM, March 5, 1989.

[x] MAD’s AGM Report, March 13, 1988.

[xi] Christine Comans Interview with Jim Vilé, June 2, 2003.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Ibid.

Tell us your story